To all my homies that get the popup on mobile:

The policy debate over climate change never stops, so when Los Angeles caught fire a few days ago, the finger pointing over who or what to blame quickly followed. I thought it would be helpful to write a quick post telling you what the science tells us about the connection of these fires to climate change. What are the ingredients of a devastating fire?

Fires like the one in LA emerge through a sequence of climatic events:

The cycle typically begins with periods of significant rainfall, which promotes vegetation growth and biomass accumulation: in Los Angeles, they had an incredibly wet 2024 winter.

When this wet period is followed by prolonged dry conditions and elevated temperatures, the accumulated vegetation dries out, turning it into rocket fuel for a wildfire: in Los Angeles, they had an incredibly dry and hot summer 2024, and basically no rain since.

Finally, you add an ignition source and strong winds to spread the resulting fire: There are always ignition sources, both human and natural, that start the fire. Santa Ana winds spread the fire, and made it basically impossible to fight.

How is climate change affecting fires like the one in Los Angeles

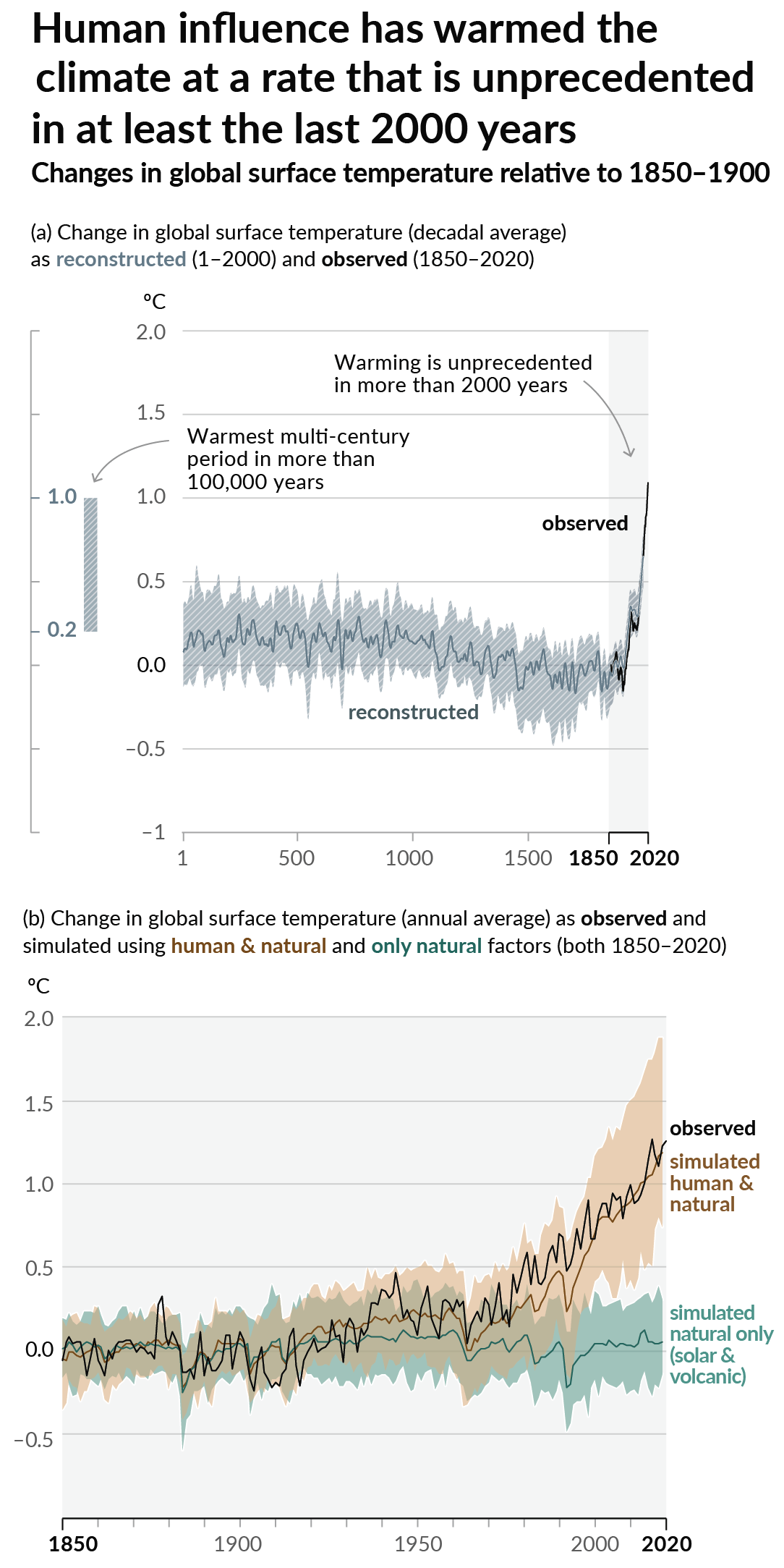

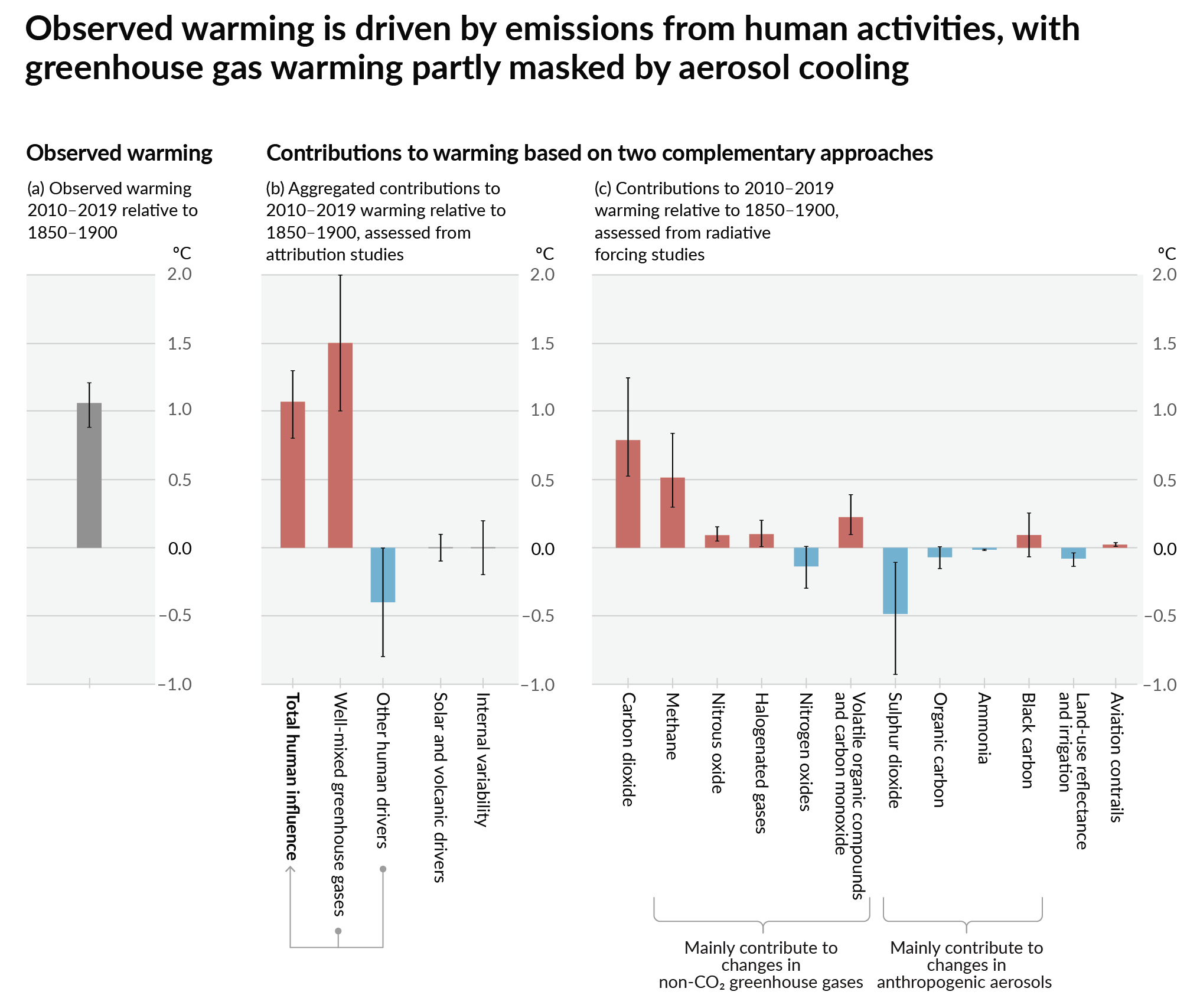

Climate change doesn’t cause any of these factors. But climate change can affect them. For example, we are confident that climate change is making rainfall more variable, with bigger swings from wet to dry extremes. This promotes vegetation growth and then drying it out. Additionally, humans are also causing a warming of the climate system, which accelerates the drying of vegetation by increasing evaporation rates and extending drought periods.

In this way, climate change is turbocharging the wildfire just like it turbocharges heat waves and hurricanes.

Of course, other factors also play a role, such as the amount and arrangement of available fuel. Forest management practices over the past century have led to accumulations of understory vegetation and dead organic material in many forests. The expansion of cities into wildland areas introduces more potential ignition sources, adds structures and infrastructure that can fuel fires, and creates zones where preventive measures like prescribed burning are challenging to implement.

Climate misinformers often exploit these multiple contributing factors to downplay climate change’s role. They present a false, illogical choice: “If poor forest management is to blame, then climate change can’t be playing a role.” The best available science tells us otherwise — climate change’s influence on fire behavior has grown increasingly significant in recent decades, amplifying the effects of any management decisions or human development patterns. In the media …

Unfortunately, many media outlets continue to rely on outdated scientific caveats about linking extreme weather like this wildfire to climate change. Link

Climate change does not “cause” extreme events, but it can amplify them. In fact, it is certain that climate change affects every weather event by altering the baseline conditions in which they occur.

Thus, the real scientific question is not whether climate change influenced the fire — of course it did. Rather, the real question is quantifying the impact: how much did climate change increase this specific event’s intensity or likelihood? We don’t know the answer yet, but I’m sure scientists are already working on it.

When reporters frame the issue as one of uncertain causation, they’re misrepresenting the science and giving climate misinformers room to cast doubt where none really exists. The recovery

Recovering is going to be really, really hard. One aspect that I think about a lot is how bad this is going to be for housing availability. When Paradise, CA burned in 2018’s Camp fire, roughly 50,000 people were displaced. About 15,000 relocated to nearby Chico — a city already struggling with a severe housing shortage.

This sudden population surge triggered multiple waves of housing instability: wealthy fire survivors quickly bought up available homes in Chico, causing housing prices and rents to spike; landlords in Chico evicted their residents so they could sell their properties in the booming market; and those who couldn’t afford the inflated prices ended up homeless. While fire survivors received some disaster assistance, those indirectly displaced by the resulting housing crunch got no help.

The crisis exposed how climate disasters can amplify existing housing vulnerabilities — Paradise had historically served as a destination for people priced out of Chico, and its destruction eliminated that crucial safety valve, leaving many with nowhere affordable to go. This fire will be bad news for the LA housing market.

If you want to learn more about the housing problems that followed the Camp fire, listen to this episode of 99% Invisible, one of my favorite podcasts1. The stories of people displaced and unable to find housing in that episode are heartbreaking. Insurance

I find myself talking incessantly to anyone who will listen that home insurance is becoming a climate-fueled catastrophe. For example, here’s a Climate Brink post about it.

Insurance companies are already reducing their exposure to risk in California and there’s absolutely no doubt that this event is going to make it both harder and more expensive to get insurance there. This is also happening in Florida because of hurricane risk.

Rising insurance costs may ultimately make it too expensive for many people to stay in their homes. In places like California and Florida, this is forcing residents to go without coverage, accept bare-minimum policies that don’t actually cover recovery costs, or pay astronomical premiums that consume an ever-larger share of their income.

The ripple effects extend far beyond individual homeowners — without affordable insurance, businesses struggle, property values decline, local tax bases erode, and entire communities can face economic instability. This insurance crisis represents one of the first ways that climate change is systematically harming economies, long before the physical impacts of warming fully materialize. A final thought

I’ll leave the final thought to a friend who lives in LA, who wrote this in an email:

This is a catastrophe on a scale that is difficult to imagine, even if we scientists know the statistics increasingly favor these scales of destruction.