Found this weird ant on our table, it has a very big head. Does anyone know what type of ant this is? (Found in New Zealand). Im guesing because of its large mandibles its probably not a worker ant instead perhaps its a soldier.

Also I just learnt the different forms of an ant (queen, worker, soldier) are called castes.

This creepy crawly was found living in a rarely used toilet in Brussels.

I was alarmed to find it. Is it a parasite? Hookworm, or roundworm?

Some history:

This is a rarely used part of the house. One day I discovered the toilet bowl was teeming with sewer drain fly larvae. Also creeped me out until I worked out what I was looking at. I’m not bothered about drain flies so I just left it alone. Returned to the toilet a couple months later and the trap was bone-dry. There was a hard blob of something.. mud, limescale, I don’t know. Not sure how it got there. It was the size of a golf ball so more mass than I would expect from limescale. I used a strong acid to descale the toilet. I made the toilet sparkling clean.

Then I used the trap to clean a dread-lock style mop because I could stuff it in there and squeeze out the the grime. And the mop could also reach deeper into the trap to clean the toilet better. Toilet water would become instantly black but easy to flush and repeat. After 10 or so iterations the water was still gray so I gave up.. maybe the mop should be bleached.. so I put the mop away. The mop was previously used to clean up cat urine (neighbors cat keeps entering my house, peeing on the livingroom floor and stairs, then bailing.. does not hang-out [why mark in a territory it does not intend to use?]). Anyway, I did not defecate in the toilet after cleaning it. Maybe urinated a couple times over the span of a couple months.

Then out of the pure blue I find this creepy crawly. Should I bring this thing to a doctor? I cannot work out how it got there or if it came from me. Perhaps equally important are the sand grains (50 or so?) around it.

theory 1: it entered the cistern from the Brussels water supply, perhaps as an egg. Hatched in the cistern. Brussels water contains sand which builds up at the screens of the tap airators and also in the cistern. A typical flush does not bring any noticable sand into the toilet bowl, but maybe if a worm were in the cistern it would have moved the sand around so that a pinch of sand would go in a flush, along with the worm.

theory 2: it came in from the Brussels water supply and ended up in the sewer pipes like most of the water does, grew in the sewer pipes and crawled up into the toilet trap from the sewer side. As it crawled, sand and scum from the sewer pipe stuck to it and washed off it when it entered the trap.

theory 3: it came out of me and ended up in the sewer pipes and crawled into the toilet. No!!! I hope not. But if so, it’s the lower floor toilet that I use, so the worm would have to do a straight up vertical climb 1 story high inside of PVC. Seems unlikely.

theory 4: I leave the window open most of the time and the toilet seat up, so a bird could have flown in and dropped something in the toilet.

They all seem unlikely.

These are quite common in Yucatan, Mexico.

The leatherleaf slugs belong to the family Veronicellidae. This particular one could be Sarasinula plebeia, but it is not so easy to definitively ID these.

I originally identified this species a few years ago from the description on this website, but since then they have added an update stating that my original source is also unsure on this one.

UPDATE: It seems that IDing certain slugs by pictures isn’t a good idea. In 2024 when pictures on this page were uploaded to iNaturalist, another user suggested a different species in the genus Leidyula, and then user “deneb16,” a mollusk specialist at UNAM, Mexico’s main university, added the comment that all Mexican species of the family this slug belongs to can’t be identified without dissecting their sexual organs. The family, she agrees, is the Leatherleaf Slug Family, the Veroncellidae.

So, I am not 100% of the species, but it is a leatherleaf slug.

Main image, by Eoperipatus sumatranus, Mok Youn Fai

Above, Peripatus sp, by Susan Myers

There are around 180 species of Velvet Worm

Above, A selection of velvet worm species from Australia. Original photographs by Jenny Norman, Noel Tait and Paul Sunnucks, from here

They live in moist, dark places in the tropics, as well as Australia and New Zealand

Above, Velvet worm (Peripatoides novaezealandiae), by Frupus

Velvet Worms have changed little in the last 500 million years with fossils of marine versions being found from Cambrian Era rocks (Burgess Shale, Canada 505 years ago, and the Chengjiang formation, China (520 million years ago))

Above, Euperipatoides sp, by Edward Evans

They have hydrostatic skeletons, comprised of muscle layers and the body wall. It's body cavity is filled with fluid, which is pressurised and keeps the body rigid!

Above, Peripatus sp, by Paul

They move by alternating the internal fluid pressure in its limbs as they extend and contract along its body!

Their skin is waterproof and is covered with papillae- tiny protrusions with bristles which are sensitive to touch and smell!

Above, Velvet worm (Eoperipatus sp.) by Nicky Bay

The papillae are composed of overlapping scales, which gives the Velvet Worm its velvety appearance!

Above, Skin of Euperipatoides rowelli, by Andras Keszei

Their feet are described as conical, baggy appendages. At the end of each foot is a hooked claw made of chitin, the Velvet Worms scientific name is Onychophora, meaning 'claw bearers'

Above, Onychophoran legs and claws, by alexselemba

Above, Onychophora, by Nicky Bay

They only use the claws on their feet when walking on uneven surfaces, they can retract these claws and use its foot cushion at the base of the claw

Depending on the species, a velvet worm can have between 13 and 43 pairs of feet. The feet are hollow, fluid-filled, and have no joints.

Above, Peripatoides novaezealandiae, by Frupus

Velvet Worm species can vary in length from 10mm long to ones in excess of 20cm

Above, velvet worm to scale, by Andras Keszei

They have a pair of sensory antennae on their heads, and small eyes. The mouth has a set of jaws, and is flanked by two papillae

Above, photo by melvyn yeo

They prefer to live in moist areas, hiding in the soil, or under rocks and rotting wood... and they like to come out at night and during wet weather

Above, Ooperipatellus species, by Simon Grove

They hunt at night for small invertebrates, and are ambush predators. They have a pair of glands on their heads near to the antennae which squirts out a sticky, quick hardening slime!

Above, Eoperipatus sumatranus? by Nicky Bay

Above, via Daily Dot

The slime ensnares their prey, allowing the Velvet Worm to inject a digestive saliva through its bite... this liquefies insides of its prey making it easier to eat! It will also eat any left over slime as it is energetically costly for it to produce

Above, by Miguel "Siu"

One species (Euperipatoides rowelli) is social! It lives in groups of up to 15 individuals, and has a strict social hierarchy with a dominant female!

Above, Velvet worms (Euperipatoides rowelli)- Captive individuals. A couple babies can be seen in this image, by Jackson Nugent

After a kill the dominant female feeds first, then the other females, the males, and finally the young... the hierarchy is strictly enforced and maintained via aggression (biting, chasing, kicking and crawling over subordinates!)

All Velvet Worms reproduce sexually except Epiperipatus imthurni which reproduces via parthenogenesis! No males have ever been found... only females!

Above photo (Epiperipatus imthurni), by Geoff Gallice

Sexual reproduction can be quite varied amongst the species of Velvet Worms.... some males will deposit their spermatophores directly into the female's genital opening. Other use a special structures on the head, whilst some use spikes, spines, or pits to either hold their sperm or transfer it to the female!

Above, Metaperipatus inae, by Art

Male Peripatopsis Velvet Worms will deposit their spermatophore on random areas of the females body. The sperm causes a small, localised breakdown of her skin, allowing the sperm to enter her body. It then migrates to her ovaries, and fertilisation takes place!

Birth can be as varied as reproduction. Some species lay eggs. Peripatopsis mothers retain eggs in their uteri and supply nourishment to their embryos, but without any placenta....Most velvet worms however, give birth to live young after a period of gestation their via a placenta. All young are born/hatch fully developed, and look like mini adults!

Above, Peripatus-sp, by Pedro Bernardo (Peripatus mothers supply nourishment to their embryos through a placenta)

Euperipatoides rowelli just "born" (not sure what the term is for oviviparous animals), still in the egg membrane it developed in inside it's mother. The egg is approximately 2mm in diameter

Above, Euperipatoides rowelli, Andras Keszei

Goodbye, Velvet Worm!

Above, Eoperipatus sp, by Nicky Bay

Info via wired and wikipedia here and here

As always my usual disclaimer.... I'm no expert, I just like learning and sharing information, any mistakes will be mine and I'll correct them if you leave a comment 👍

Main image, While Gotham sleeps........ by Michael Gerber

RED...

Above, Pseudoceros ferrugineus, by Benjamin Naden

PINK...

Above, Protheceraeus roseus, by João Pedro Silva

YELLOW...

Above, Eurylepta sp. by Karen Honeycutt

ORANGE...

Above, Pseudoceros sp. by Rafi Amar

BLUE...

Above, Racing Stripe Flatworm - Pseudoceros liparus, by Rafi Amar

PURPLE...

Above, Linda's Flatworm - Pseudoceros lindae, by Rafi Amar

BROWN...

Above, Photo by Nick Hobgood

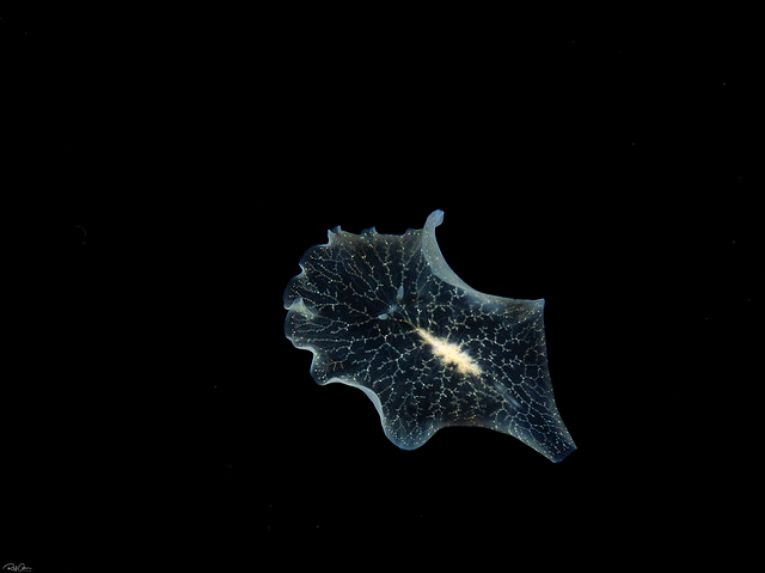

TRANSPARENT...

Above, Paraplanocera sp. by Rafi Amar

SALAD...

Above, Cryptic Flatworm - Pseudobiceros kryptos, by Rafi Amar

GOTH...

Above, Photo by Bettydiver

NEON...

Above, Pseudoceros dimidiatus, by Richard Ling

STARRY...

Above, Thysanozoon nigropapillosum, by Patomarazul

TRIPPY...

Above, Persian Carpet Flatworm - Pseudobiceros bedfordi, by Rafi Amar

GLITTERY...

Above, Photo by eunice khoo

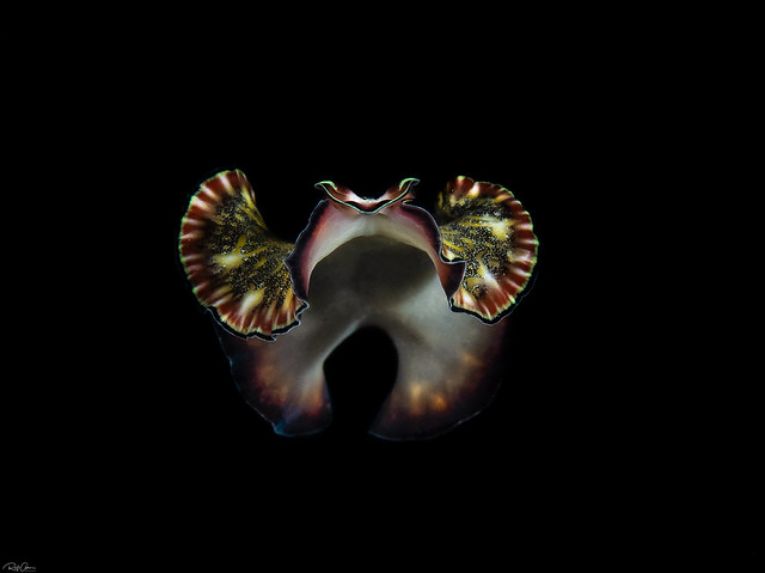

FRILLY...

Above, Glorious Flatworm - Pseudobiceros gloriosus, by Rafi Amar

STRIPEY...

Above, Pseudoceros zebra, by Marina Poddubetskaia

SPOTTY...

Above, Pseudoceros scintillatus, by ilan Lubitz

VEINY...

Above, Eurylepta californica, by Robin Gwen Agarwal

BRAINY...

Above, Maritigrella fuscopunctata, by Rafi Amar

SANDY...

Above, Pseudobiceros damawan, by Rafi Amar

CAKEY...

Above, Lizard Island Flatworm - Tytthosoceros lizardensis, by Rafi Amar

CAMOUFLAGEY...

Above, Flatworm - Paraplanocera sp. by Rafi Amar

HOLSTEIN-FRIESIANY...

Above, Eurylepta sp.1, by Rafi Amar

AMBUSH RUG...

Above, Photo by eunice khoo

GOODBYE, FLYING FLATWORM!

Above, Persian Carpet Flatworm - Pseudobiceros bedfordi, by Rafi Amar

edit- Forgot to do the thing that makes the image pop out when you click on it.....

Main image, Oleander Hawk Moth Caterpillar (Daphnis nerii, Sphingidae), by itchydogimages

Startled? Alarmed? Did I hear you mutter "WTF?" under your breath?

Then evolution wins again. Imagine if you were confronted by the same sight if you were a bird or a praying mantis or a snake for that matter. Eyespots (markings that resemble vertebrate eyes) have evolved many times in Lepidopterans (butterflies and moths). The fact that this adaptation has arisen independently so often in this group indicates the general effectiveness of this anti-predator defence. itchydogimages

Above, Walking forest, by Gabriela F. Ruellan

Above, Moth Caterpillar - Cerura vinula, by Lukas Jonaitis

I took this photo last summer. This caterpillar is one of the most beautifull caterpillars in Lithuania. I think it is very photogenic caterpillar because of its green colour and red tails which are visible only when caterpillar is scared. He has very nice face. :) Lukas Jonaitis

Above, Saturnia Pyri, by Jano De Cesare

This is a beautiful larva of a Saturnia Pyri, a butterfly which is around 16cm in maximum dimension at its mature state. Jano De Cesare

Above, Stinging Nettle Slug Caterpillar (Cup Moth, Setora baibarana, Limacodidae) "The Jester" by itchydogimages

First-in-line to the throne of the brilliant Yunnan lineage of Limacodid caterpillars, together with its alternate colour form, "The Clown", "The Jester's" livery is almost fluorescent. itchydogimages

Above, Stinging Nettle Slug Caterpillar, Limacodidae, by Andreas Kay

Above, 3rd Instar Cecropia, by Barb Sendelbach

Above, Big Foot (Cecropia), by MaggieDu

Above, Photo by Frank Starmer

Above, Dalceridae moth caterpillar, by Gerardo Aizpuru

Dubbed the 'jewel caterpillar', this lovely, translucent larva belongs to a family of moths known as Dalceridae. Although scientists are still unsure about the exact function of the caterpillar's translucent, gooey attributes, the leading theory is that the slimy stickiness helps to deter predators. According to Scientific American, the jelly-like 'cones' that cover the body break off easily (sort of like a lizard's tail), helping the caterpillar slip out of a predator's clutches. source

Above, Flannel moth caterpillar, by Drriss & Marrionn found here

It may look like Donald Trump's misplaced toupee (it's actually been dubbed the 'Donald Trump caterpillar'), but this flannel moth larva is actually not covered with hair at all. Those silky-looking threads are actually venomous spines that can cause intense, burning pain when touched, making the caterpillar one of the most venomous in the US. source

Main Image of....

....three species of tunicates ("sea squirts") - Polycarpa aurata is purple and orange, Atriolum robustum is green, and the blue is from the genus Rhopalaea. (Nick Hobgood)

There are around 3000 species of Sea Squirts aka Tunicates!

Above, Corella parallelogramma by Mark N Thomas

They are found in salt water throughout the world!

They are our closest invertebrate relatives!

Above, Photo by Chas Anderson

They are called Sea Squirts because if they are touched or alarmed the muscle will suddenly contract forcing the water inside to shoot out!

Sea Squirt larvae look like frog tadpoles!

Above-

A deep-water larvacean (aka “sea tadpole”) inside its mucous “house,” which concentrates food from the water prior to reaching the animal’s mouth. (Hidden Ocean 2005, NOAA)

As larvae they swim around in the ocean current, and when they find a food rich environment they use sucker to attach to a rock, dead coral, boat dock, or mollusk shell!

Above, Photo by prilfish

Then they begin metamorphosis!

Above-

Tunicate larvae resemble tadpoles (developing frogs). (Van Name, 1945)

Their notochord begins to shrink and is absorbed into the body, the tunic forms as the transformation continues and finally it becomes an adult Sea Squirt!

As an adult it will now feed on tiny particles found in the water, primarily bacteria!

Above, Blue Bell Sea Squirt (or Tunicate) - Perophora namei by Jim Greenfield

There are two types of sea squirts- solitary and colonial!

Both have 2 siphons. The Oral Siphon receives the nutrient content in the water, and the Atrial siphon excretes the waste!

Colonies are formed when a newly settled larvae changes into an adult. It then splits or 'buds' producing new individuals!

Above, Clavelina sp. by Jim Greenfield

Colonies can range from a few centimetres to several metres depending on food supply and predation!

Colonial Sea Squirts share a common tunic and sometimes and also sometimes share the atrial siphon!

They have a digestive system similar to ours, complete with an esophagus, stomach, intestines and a rectum!

Sea Squirts act as ocean purifiers, as they consume bacteria. They can also absorb zinc and vanadium, indicating heavy metal presence within their ecosystem!

Above [An obligatory Nudibranch!], Striped sea slug snacks while strolling on a sea squirt by Nick Hobgood

All photos and info found here, except where indicated!

And as always my usual disclaimer- I'm not an expert in anything, I just enjoying finding and sharing interesting things.... Any mistakes are mine and I'll correct them if you let me know in the comments 👍

edit re-uploaded main image as it wasn't showing

edit 2 changed 'ancestors' to 'relatives' in the title

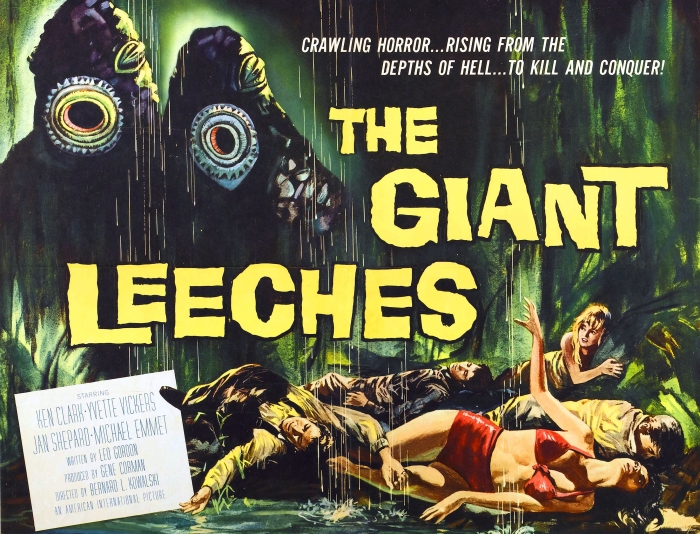

Lovely story from The Guardian

It was September 2014. I’d just started working front of house in a fancy hotel in Edinburgh. I spent most of my shifts with a paper napkin pressed to my nostril, as I had been getting lots of nosebleeds. I would soon find out why.

A few weeks earlier, I’d been travelling in Vietnam. I had rented a moped and had the time of my life driving around. I soon crashed but luckily was wearing a helmet, so only got a small bump on my head.

A few days afterwards, I started to intermittently spot blood from my right nostril. I assumed it was from the crash and didn’t think too much of it. I was 24 and too busy partying to take anything like that seriously. I danced the nights away while ignoring the persistent blockage in my nose.

Reality came flooding back after returning to cold Glasgow. Nothing had changed with my nose, so I went to the GP. The doctor told me that it didn’t sound like anything to worry about. I was advised to use Vaseline on the area to keep the nostril lubricated and was sent on my way.

A week later, I moved to Edinburgh for my job. That’s when I started to feel frustrated with my constantly stuffy nose. I wasn’t in pain, but sleeping was difficult. I would blow my nose to try to clear the blockage, but it would only lead to nosebleeds. Things started to get particularly weird when I was having showers. Through all the humidity, I could feel a thick, slimy thing moving down my nose.

I had a day off work; it had been a month since I returned from abroad. My friend Jenny was coming from Glasgow to meet me for dinner. I was in the shower when I felt the all-too-familiar feeling, but this time I glimpsed something hanging out of my nostril. I jumped out and raced to the mirror, frantically wiping off the steam. I saw a clot hanging out – then recoiled in horror when I saw ridges running along a thick black body.

I rushed out of the house to see my friend, screaming, “It’s a full-on worm!” Jenny knew about the problems I’d been having with my nose, but she didn’t believe me at first. I stuck my nose in the air so that she could see for herself. Her mouth hung wide as she gaped and said: “Yep, there really is a worm in there.”

At first, it was the most hysterical thing that had ever happened to us. We couldn’t stop laughing. Because it had been in there for so long, I felt very blase about the whole thing. We rang the NHS helpline. The call adviser was crying tears of laughter over the phone, as it was the most bizarre thing she’d heard.

We went to A&E. Doctors were bewildered and didn’t take me too seriously at first. But once the nurse looked up my nose, she gasped. I was placed on a gurney as they stretched my nostril open with forceps. The doctors spent 30 minutes using different tools to try to prise the leech away. Leeches release an anaesthetic when they bite so they can stay on a body for longer, which is why I couldn’t feel the pain before – but it was agony when the doctors tried to pull it out. When they finally succeeded, I felt a wave of cold air shooting through the blocked nostril. It was like being in a nightmare, seeing the leech held up high, squirming. It was longer than my finger.

I’d swum a lot on holiday, so we guessed that it most likely came from there rather than having anything to do with the motorcycle accident. The leech was put in a jar and sent to a specialist hospital in London for further testing – they were worried that it may have passed on further diseases to me. Suddenly, something that was so funny seemed much more serious.

Luckily, all of my tests came back clear, and I had no side-effects. I was given the leech back in a pot and told to dispose of it. The leech was rock hard because it had so much of my blood inside. It made me squirm just looking at it.

Now, a decade later, the story of the leech and me has become a go-to anecdote whenever I meet someone new. I even had someone message me on LinkedIn recently asking about it. So while the leech was attached to me in a very physical sense, I guess we’re still attached metaphorically. But I’m very glad it’s out.

Main photo by Ocean Networks Canada

Above photo via MBARI

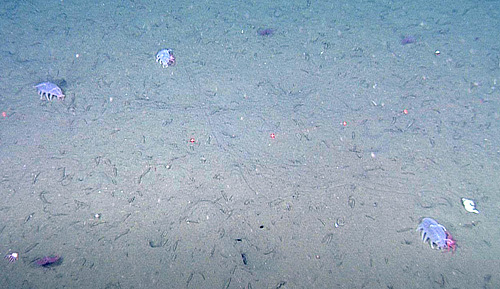

Sea Pigs (Scotoplanes) are a type of Sea Cucumber

They live in the deep sea, specifically on the abyssal plain up to depths of 5000m

They can grow up to 4-6 inches

They have 6 pairs of enlarged tubal 'feet', and use water cavities in their bodies to inflate and deflate them in order to move around, as well as ten buccal tentacles lining their oral cavity

Above photo via Ocean Networks Canada

They live on the sea floor feeding on delicious foods such as decaying animals, poo and mucus!

If they are disturbed they can swim! In fact some Sea Pigs spend most of their lives swimming around in the water column using their frontal and anal lobes to propel themselves around!

They will gather in large numbers around whale corpses to feed and perhaps find a mate

Above, a congregation of Sea Pigs feeding on a whale carcass via MBARI

Their reproductive system is unique, the males only have one testis, and the females one ovary!

Also their skin contains a toxin called holothurin which is poisonous to predators...

They have a poorly defined respiratory system, and have to breathe through their anus!

Above photo by Oceans Network Canada via Treehugger

As they have evolved at deep sea depths they would swell and burst if brought to the surface

They are hosts to several parasitic invertebrates, including snails and small crustaceans

But wait! What's this...?

Above Above photo via MBARI

What's that red thing hiding under the Sea Pig?

Above photo via wikipedia

It's a King Crab!

Above photo via MBARI

Peek-a-boo!

Above photo by Josi Taylor via MBARI

Why do King Crabs ride on Sea Pigs?

Usually King Crabs like to hide in rocks and seaweed from predators, but it is thought that these King Crabs were carried by the ocean current while they were small larvae and ended up in the deep sea....an area devoid of such hiding places!

“It’s like looking for a port in the storm,” said James Barry, ecologist and lead author of the study at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) in Moss landing. Sea cucumbers are the ports or the biggest buildings to hide next to in an otherwise empty area.” Scientific American

Above, ' This photograph of the muddy seafloor offshore of Monterey Bay shows three Scotoplanes sea cucumbers, at least two of which are host to juvenile king crabs.' MBARI

Barry and his team found a total of 600 juvenile crabs, 96 percent of which were either clinging onto sea cucumbers or hanging around right next to them. Sometimes the crabs were upside down holding onto the belly of the sea pig and other times they were crawling on its side. In some cases, the researchers found more than one crab on a sea cucumber. Of the nearly 2,600 sea cucumbers videotaped, 22 percent had at least one juvenile crab clinging to them

Goodbye Sea Pig, and your King Crab jockey!

Above photo via MBARI

edit- I completely forgot to add my sources.....wikipedia and MBARI, unless specified

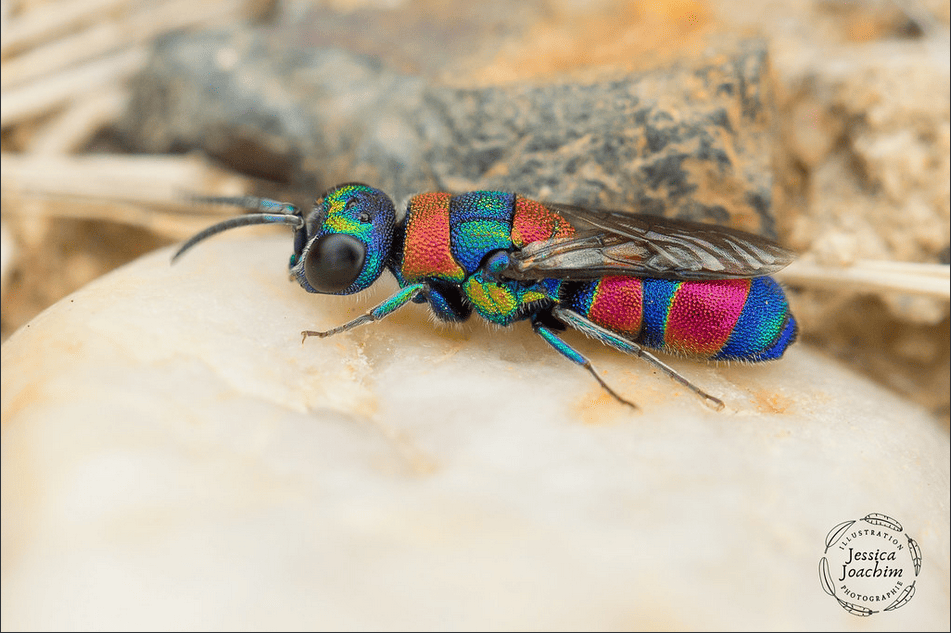

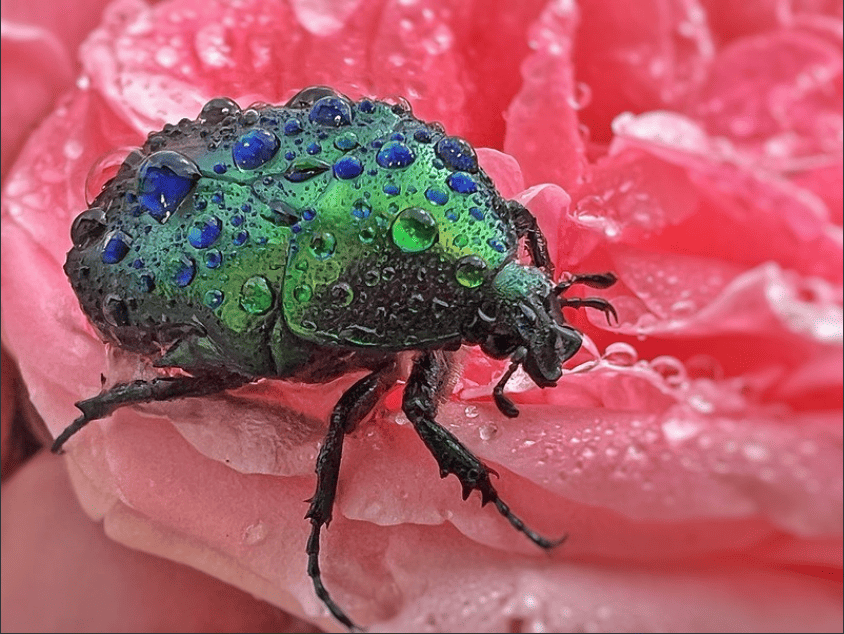

Main photo by Dusan Beno

Above, 'Chrysis semicincta' by Jessica JOACHIM

Above, 'Cotinis Mutabilis, also known as the Figeater Beetle' by Cotinis Mutabilis

Above photo by philux66

Above, 'Green Tortoise Beetle, Cassida viridis' by Duncan Cooke

Length; 7 - 10mm.

Distribution; Widespread in England and Wales, although sparse in the north and rarer in Scotland.

Habitat; Grassland, Heathland & Moorland, Farmland, Wetlands, Woodland & Gardens.

Found; April to October.

The Green Tortoise Beetle is one of a group of several closely related beetles. Host plants include White Dead-nettle, Hemp Nettles, Hedge Woundwort, Gypsywort and Water Mint and is often found in gardens. When disturbed, the adults behave just like tortoises, retracting their antennae and feet, and pulling their 'shell' tight down around them as they grip tightly on to the leaf they are.

The Green tortoise beetle is round, flattened and lime green. Tortoise beetles are easy to identify as a group, but there are several closely related species that are very difficult to tell apart. the Green Tortoise Beetle is entirely green and generally lacks the markings of other species. Cassida viridis is similar to Cassida rubiginosa but can be distinguished by the rounded rear corners of the pronotum which are sharp in C. rubiginosa. It is also usually more apple green in colour.

Adults spend a few weeks feeding on host foliage and possibly also pollen before mating in April and May and ovipositing from May to July. Between 1 and 10 eggs laid in firm-walled and distinctive egg cases which are stuck to stems or under lower leaves and covered with frass and leaf fragments. They hatch within 6 to 10 days and the larvae initially feed below the leaves, moving to the upper surface as they grow, they pass through 5 instars and develop rapidly. They are fully grown within 4 to 6 weeks.

Pupation occurs from June to September. The fully grown larvae move to stems and petioles and become attached by a secretion before they pupate. This stage is also brief, generally lasting about a week, and new generation adults emerge from July to October.

Above 'Green vegetable or Shield bug' by Bernard Spragg. NZ

Nezara viridula, commonly known as the southern green stink bug, southern green shield bug or green vegetable bug, is a plant-feeding stink bug. Believed to have originated in Ethiopia, it can now be found around the world.

Above, 'Golden Beetle' by Ivan Anisimov

-Leeches are found all across the world, except Antarctica, so far around 700 species of leech have been described. Approximately 100 are marine, 480 freshwater and the remainder are terrestrial different species…. All of these are divided into 2 major infraclasses

Euhirudinea: the 'true' leeches – marine, freshwater and terrestrial – which have suckers at both ends and lack chaetae (bristles)

Acanthobdellida: a small northern hemisphere infraclass ectoparasitic on salmoniid fish, which lack an anterior sucker and retain chaetae.

The Euhirudinea is further divided into two orders:

Rhynchobdellida: jawless marine and freshwater leeches with a protrusible proboscis and true vascular system

Arynchobdellida: jawed and jawless freshwater and terrestrial leeches with a non-protrusible muscular pharynx and a haemo-coelomic system. source

Above image from here

-Leeches are segmented parasitic or predatory worms, and are closely related to earthworms

-They have suckers at both ends of their bodies and use them to travel around by ‘looping’ or ‘crawling.’ Some species can also swim like an eel

Above image by Chiswick Chap via wikipedia

-All leeches are hermaphrodites, although they prefer to find a mate to exchange sperm packets with…..

-They can live in both fresh and salt water, and there are some which are terrestrial, living on the ground or on low growing plants waiting for a meal to brush past

-Some species can even survive extremely dry conditions by burrowing into the soil where they can stay without any water. Their bodies contract, becoming dry and rigid, but within 10 minutes of water contact they emerge, ready to go!

-The most famous type of leech is probably the European medicinal leech (Hirudo medicinalis), which was used extensively in the past (the first recorded case being Ancient Egypt 3500 years ago). Its populations in the wild have dropped significantly due to over exploitation for the medical industry

Photo by Neil Phillips

-Manchester Royal Infirmary used 50,000 leeches in one year in 1831, but use of the medicinal leech started to decline during the late 19th century. However, since the 1970’s they have made a comeback due to their use in micro surgery. Their anti coagulant saliva allows blood to keep flowing, and wounds to stay open during reattachment and reconstructive surgery!

Photo by Armando Caldas

-Hirudo medicinalis are ‘jawed’ leeches (Gnathobdellida). They have 3 jaws resembling rotary saws which have around 100 sharp edges used to incise the host which leaves a Y shape wound on the skin. They are so tiny their bite is virtually painless. Blood suckers are only one type of leech though...

-Other species of jawed leeches can have between 1 and 3 jaws. Detrivorous species use their jaws for chewing and swallowing soft food particles, whilst the carnivores use them to cut a hole in the body walls of invertebrate prey (molluscs, worms, insect larvae), in order to suck out the soft innards.

Photo by Manuel Krueger-Krusche

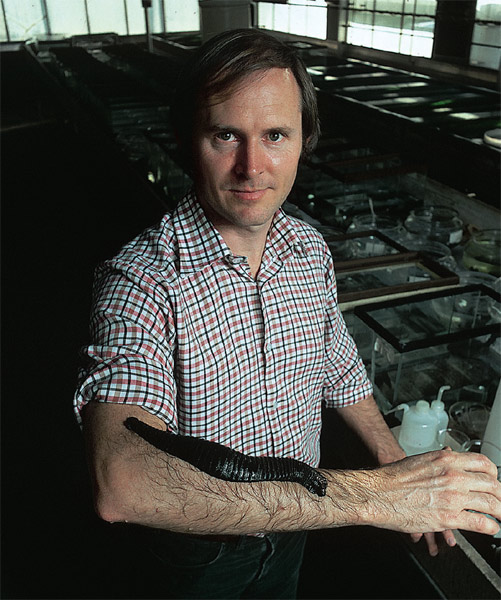

-The largest fresh water leech in the world is Haementeria ghilianii, (the Amazon giant leech) which can grow up to 450mm long and 100mm wide. One end of the leech contains its head, and the other the proboscis, which is 10cm long and like a hypodermic needle. It is capable of feeding on humans, rabbits, cattle and horses and a report from 1899 claims it could feed in such numbers that it could kill cattle and birds

Photo by Anonyme973

-Its male reproductive parts can weigh 3-5 grams, and the female parts weigh in at 10 grams, they are capable of producing egg clutches ranging from 60 to 500 eggs

-It was thought to be extinct in 1893, however during the 1970s Dr Roy Sawyer discovered 2 specimens in a pond in French Guiana. One of these was transferred to the UC Berkeley where it was part of a ‘breeding’ program. Named ‘Grandma Moses’ it managed to produce 750 offspring over 3 years, and helped to bring the Amazon Giant Leech back from the brink of extinction

Dr. Roy Sawyer and friend photographed by Timothy Branning

-When it died, ‘Grandma Moses’ was given to the Smithsonian National Invertebrate Collection where it still resides preserved in alcohol!

-A small minority of leech species have no jaws or teeth (these are the worm leeches or Pharyngobdellida). Instead they swallow their prey, usually small invertebrates, whole!

-The Kinabalu giant red leech (Mimobdella buettikoferi) is probably one of the longest leeches, growing over 50cm.

Above photo from here

-It lives only on Mt Kinabalu, Borneo and feeds on an equal giant prey, the Kinabalu giant earthworm (Pheretima darnleiensis)

Kinabalu giant earthworm, Photo by Chien Lee

Kinabalu giant earthworm, Photo by Ivan Kwan

-It lives among the leaf litter and soil, and both leech and worm are usually seen during or after a downpour….

Found here

A hungry leech is very responsive to light and mechanical stimuli. It tends to change position frequently, and explore by head movement and body waving. It also assumes an alert posture, extending to full length and remaining motionless. This is thought to maximise the function of the sensory structures in the skin. source

Photo from here

-When it finds a worm it begins to grope towards an end, then it begins to suck…..

Here is a delightful film of just that!

Also on youtube

Above photos by Paul Williams

-Almost all leeches have at least one pair of tiny eyes, however some can have up to 16, these are arranged in patterns although their vision may only be able to detect light and dark.

Photo by Paul

-Glossiphoniid leeches demonstrate exceptional parental care for their offspring, which is the most highly developed for the annelids (the worm species). They produce a membranous bag in which they keep their eggs, this is carried on the underside of their bodies. When the young hatch they attach onto their parents belly (but not with a feeding bite) and the parent carries them to their first meal!

Above photo by Maralee Joos

Above photo by Duncan Cooke

Above photo by Duncan Cooke

Helobdella, which have a world-wide distribution, display the most highly developed parental care system: they not only protect but also feed the young they carry. This results in the young being much larger when they leave the parent and, presumably, in higher subsequent survival. source

Above photo by Dick Todd

-Leeches are quite hardy, some can survive in low oxygen environments, others at low ocean depth such as….

Bathybdella sawyeri occurs at 2447–2623 m depth at the Galápagos Rift and the Southeast Pacific Rise and Galatheabdella bruuni has been found at depths of 3880–4400 m in the Tasman Sea (Richardson and Meyer, 1973; Burreson, 1981; Burreson and Segonzac, 2006). However, the leech that occurs at the greatest depth is Johanssonia extrema described by Utevsky et al. (2019) that was collected at a depth of 8728.8 m in the Kuril-Kamchatka Trench. Occurring at that depth, J. extrema withstands pressure that is over 870 times greater than that at sea level. source

-Some species have evolved to live within the extreme dark of caves, others to withstand the extreme cold of arctic waters, one lives in waters of high alkalinity with the addition of arsenic at levels >110mg/L

Members of Praobdellidae are characterized by feeding primarily from mucous membranes [mouth, throat, nasal passages, and under the eyelids] particularly of mammals, but also from the skin of amphibians. This behavior is considered equally unnerving by both academic and public audiences. source

-A backpacker returning from Vietnam discovered she had also brought home a leech passenger that was attached inside her nostril "At one point, I could feel him up at my eyebrow," she said. It was removed at Liverpool Hospital, before it could reach her brain…. She than kept the leech named ‘Mr Curly’ as a pet…. delightful!

-One other leech has evolved to live in another type of orifice...a hippos anus!

…...Placobdelloides jaegerskioeldi inhabits one of the most extreme environments of all of the leeches that invade orifices, the rectum of the hippopotamus (Oosthuizen and Davies, 1994). Adult P. jaegerskioeldi have papilla-bearing tubercules that are postulated to provide traction against the anal-wall of the hippopotamus (Oosthuizen and Davies, 1994). This species is also one of the few glossiphoniid leeches that can actively swim and swims (even upstream) to its hippopotamus host (Oosthuizen and Davies, 1994). source

As always, I’m not and expert I just like finding and sharing fun things I find on the internet. Any mistakes or errors, let me know in the comments and I’ll edit my post!

All information via wikipedia-

Except these-

Main photo 'Wasp' by Joshua Coogler

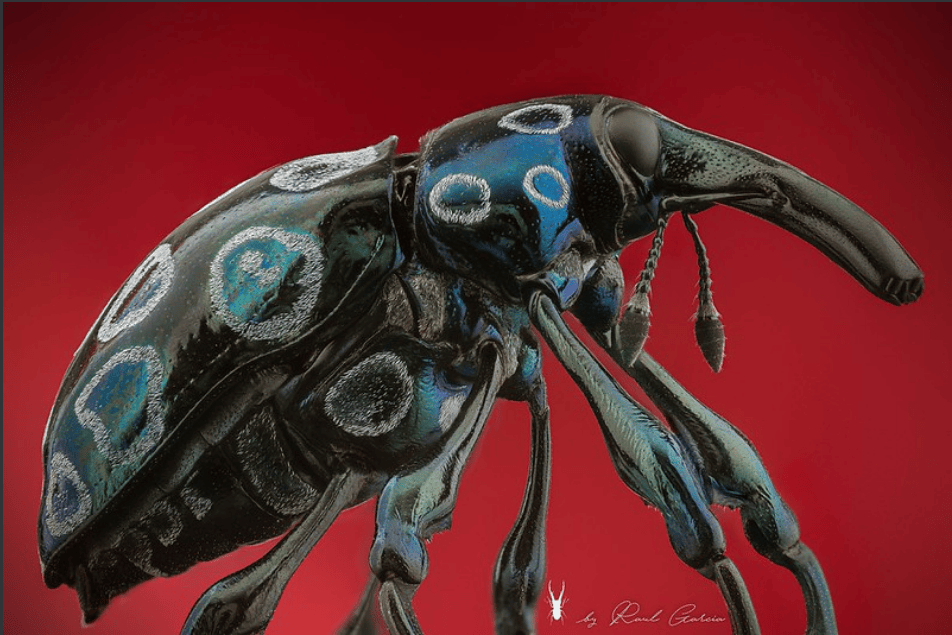

Above, 'Pachyrrhynchus ocelatus' by Raúl García Navarro

Above, 'Mite SP' by Harry Sterken

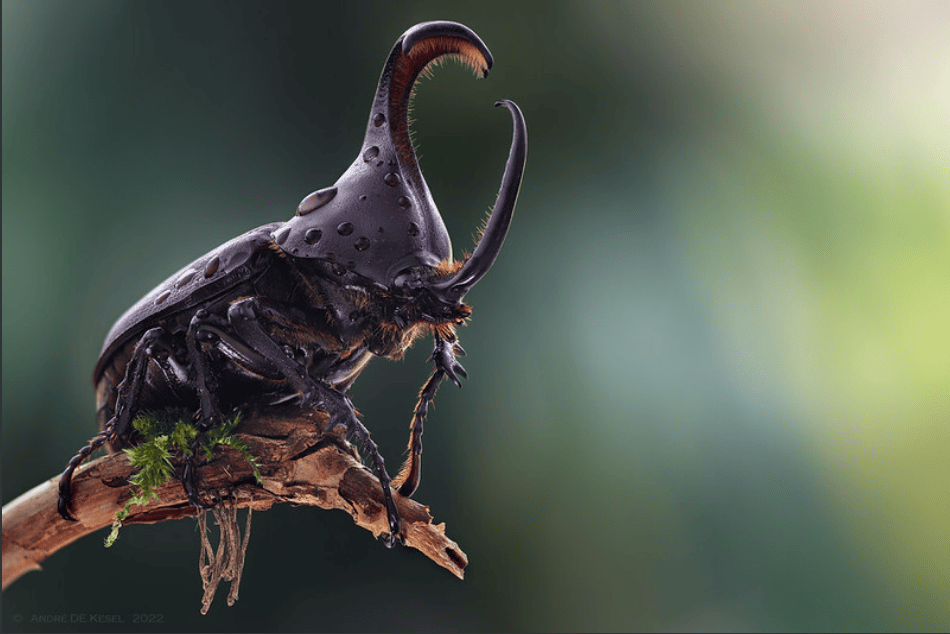

Above, 'Golofa claviger - Giant rhinoceros beetle' by André De Kesel

Above, 'Jumping spider SP (male)' by Harry Sterken

Above, 'Alcidodes Ocellatus' by Raúl García Navarro

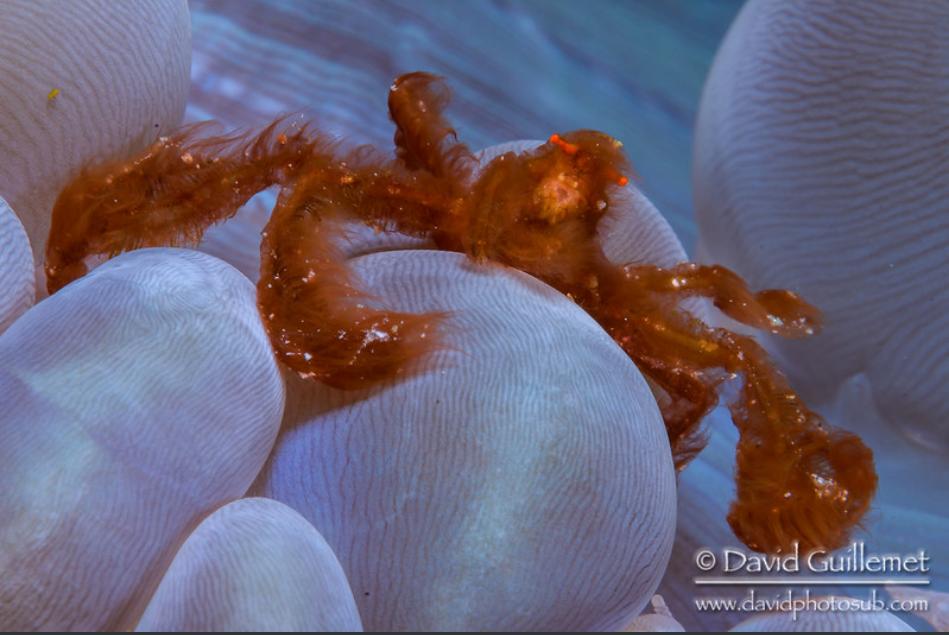

Title photo by David Guillemet

I've only just discovered that this exists...

Orangutan crab (Achaeus japonicus)

.....it has relatively long arms, which are thickly covered with fine hairs, red or reddish brown in colour, and often laden with small bits of debris for further camouflage....

....frequently, but not always, found in association with the bubble coral wikipedia

Above photo by scubaluna

-They're found in the Indo-Pacific region, have a naturally shaggy pelt, and like to decorate themselves with debris, small plants, sedentary animals, shells and gravel to enhance their natural camouflage!

Above photo by Bruce Versteegh

-During the day like to hang out in Bubble Coral, which swells its bubble-like structures to maximise its intake of light....

Above photo by Niall Deiraniya

-At night the coral 'deflates' and the Orangutan crab wanders off in search of food

Above photo by Dennis Young

The last 2 photos made me piss myself laughing....it looks like a fuzzy little muppet!

Title photo by Dotted Yeti

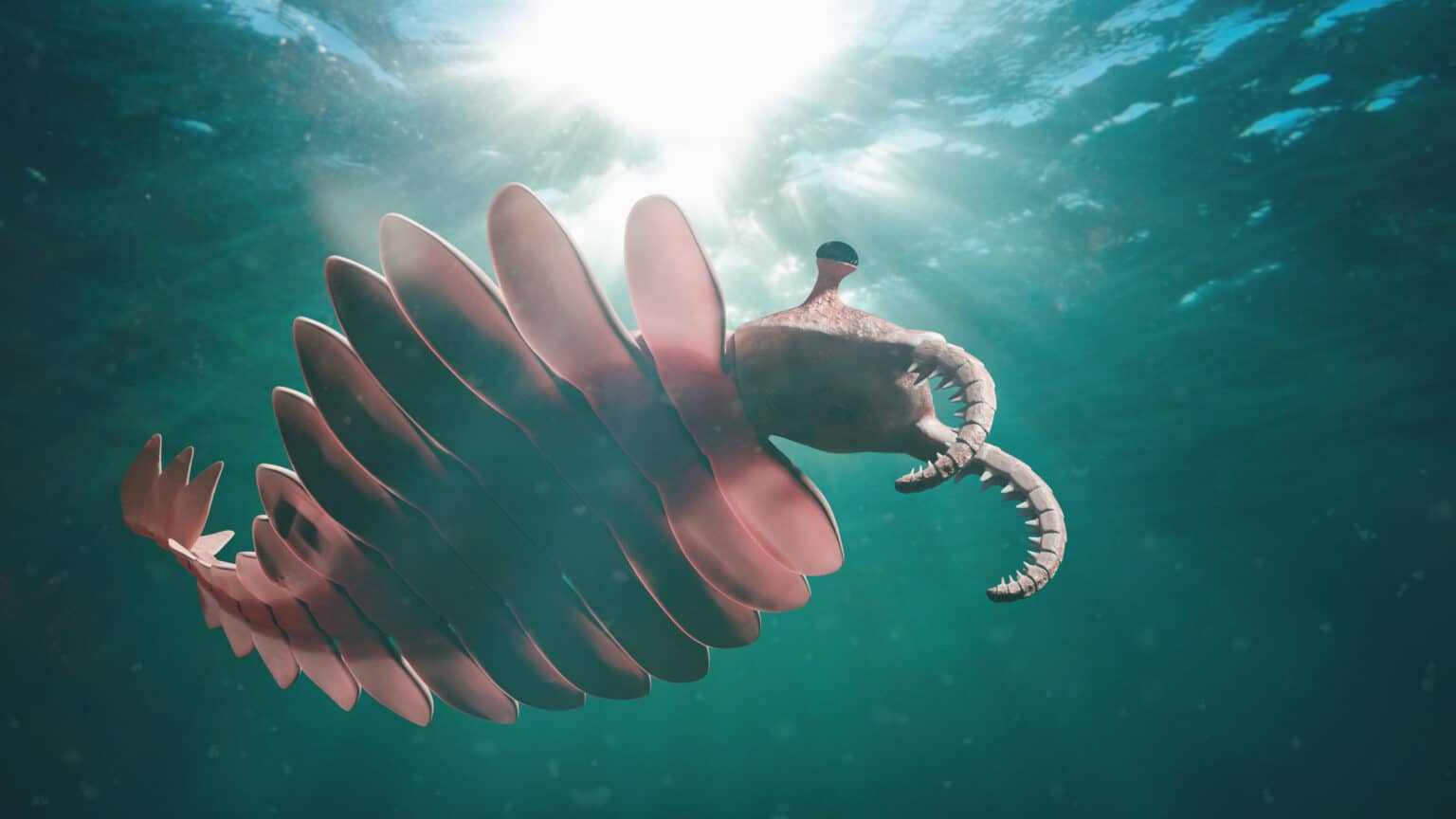

Travel back in time to the Cambrian Era, a period famous for the diversity of its life forms!

Lasting approximately 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 million years ago (mya) to the beginning of the Ordovician period 485.4 mya. It is a period where the atmosphere had elevated concentrations of oxygen, and the global temperature increased-creating a temperate world

Geological timescale from here

Scientists believe that the higher oxygen levels, and warmer climate contributed to the incredible diversity of life that occurred in the oceans.

However, on land it was mostly barren...complex lifeforms were non-existent and would have been restricted to mollusks and arthropods emerging from the water to feed on microbes in slimy biofilms

The Cambrian is unique as it had unusually high deposits of Lagerstätte sedimentary deposits, these sites offer exceptional preservation of 'soft' organism parts, as well as their harder shells which means that the study and understanding of the fossilized life forms surpasses some of later periods

(above, from my previous post on Aysheaia)

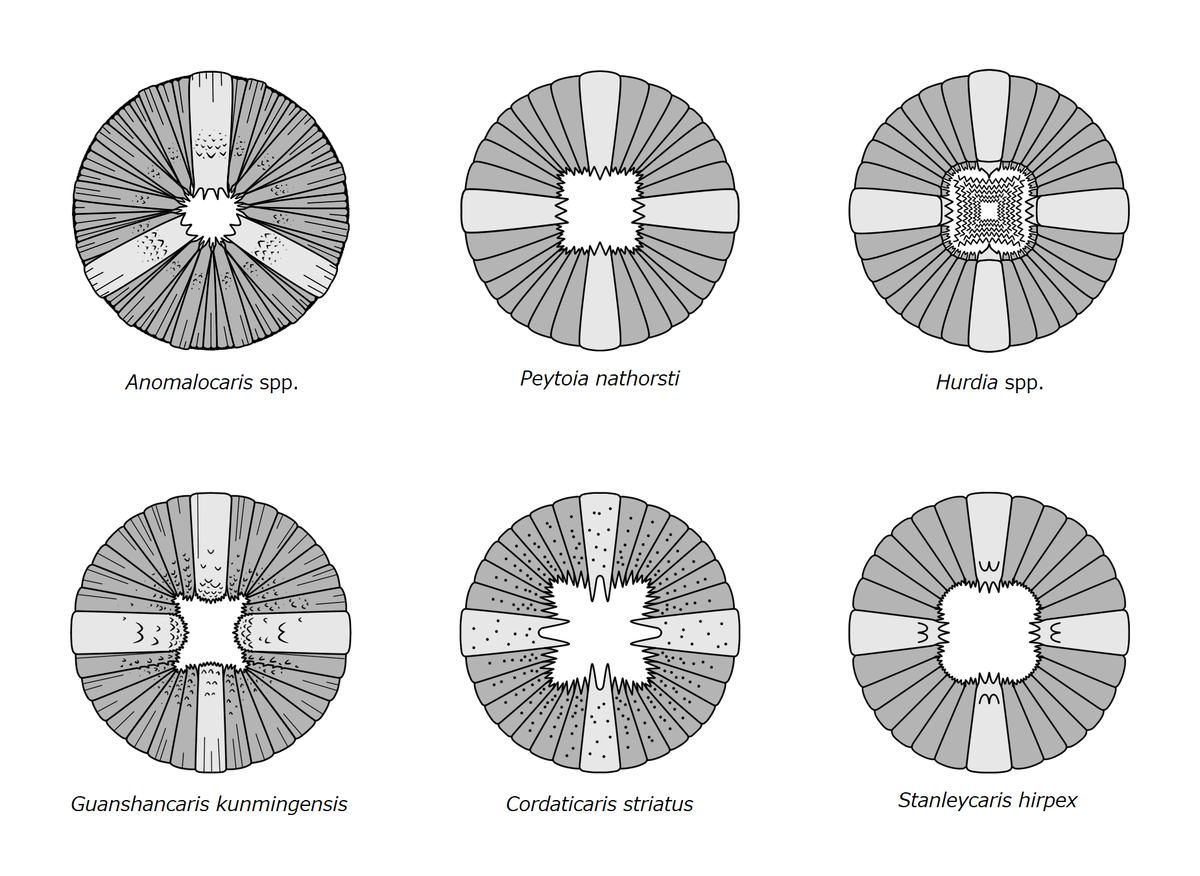

Anomalocaris means 'unlike other shrimp' or 'abnormal shrimp' and is an extinct Cambrian arthropod belonging to the radiodonts (meaning, radius 'spoke of a wheel' and odoús 'tooth') and is thought to have been one of the top predators for it's time

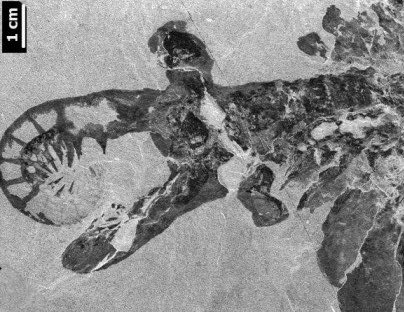

The fossils that were discovered in The Burgess Shale in 1886 were of incomplete segments and were initially thought to be 3 separate individual species. The frontal appendages were thought to be the bodies of shrimp-like crustaceans.

Above, 'named Anomalocaris ("strange shrimp") by Walcott'

The circular mouth part was thought to be a jellyfish as it showed the same radial symmetry

Above, 'circular fossil from the Burgess Shale formation was described and named Peytoia'

In 1966 a comprehensive revision of the Burgess Shale fossils began, along with additional misinterpretations which proposed that the feeding appendages were legs, and the mouth parts were part of a sponge...

However, during the cleaning of one of the fossils a layer of stone was removed which linked the feeding appendages and the mouth parts as belonging to the same animal. Later specimens showed how the feeding appendages could be curled around prey and directed to the circular mouth part, as well as eyes on flexible stalks....It had taken over 100 years of misinterpretations to finally meet Anomalocaris

Above, previously thought as the 'body of a shrimp was one of a pair of spiny grasping arms..the rim of the mouth shows partially, as does one of the large eyes' source

Above, 'appendages could curl, enfolding around prey, which was pinned by the arm spines. The captured prey was then placed into the mouth, which was under the head between the eyes. The eyes were at the ends of flexible stalks.' source

In 2021 the compound eyes made up of 16,000 lenses were discovered, proving that Anomalocaris was definitely an arthropod, and indicating that complex eyes has evolved before jointed legs or exoskeletons

Above photo by John Paterson, 'One of the stalked eyes of Anomalocaris from South Australia with arrows pointing to the boundary between the stalk and visual surface, plus the intricate lenses preserved'

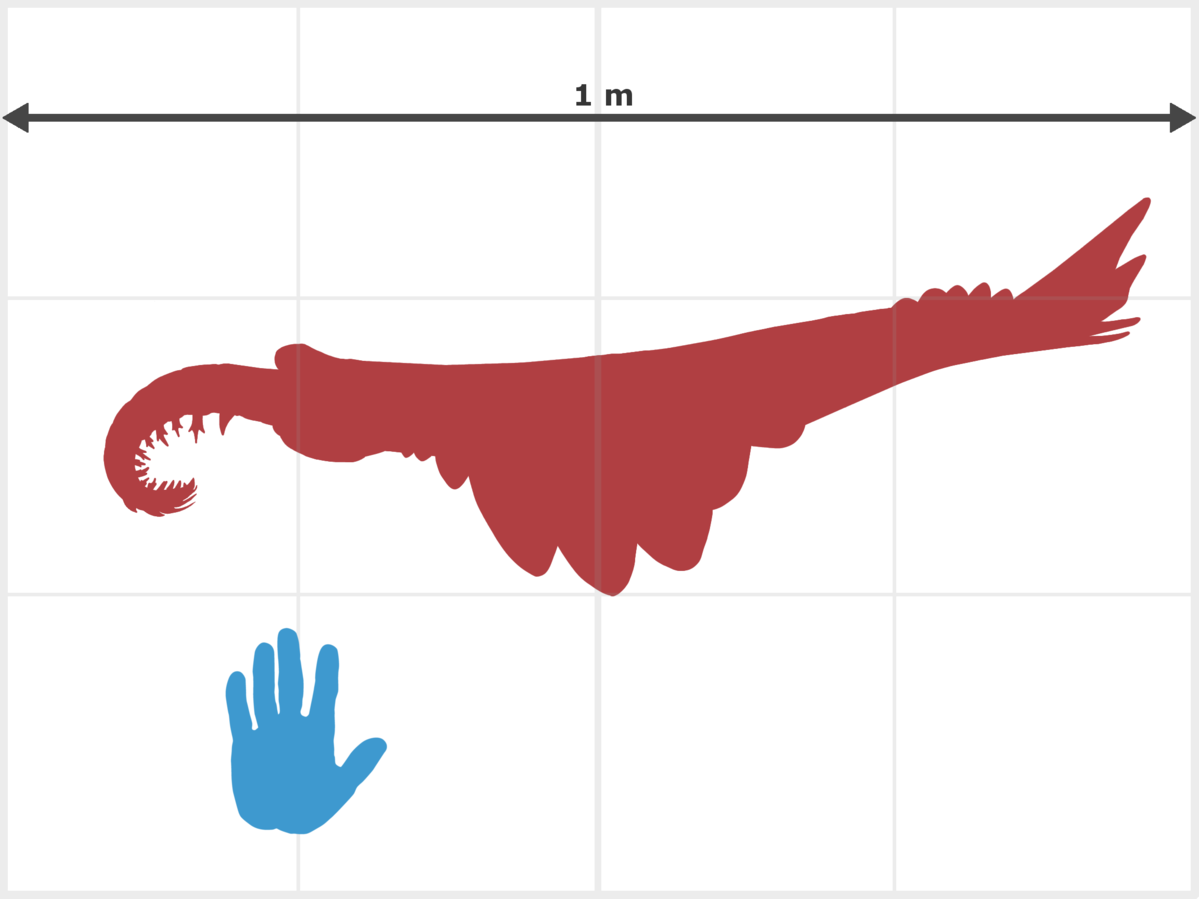

The Anomalocaris would have been huge for the Cambrian maybe up to 1 metre in length. It would have been able to swim through the water by undulating the flexible flaps on the sides of it's body chasing down prey. The compound eyes would have given it a 'high degree of visual acuity, and a well-developed brain to process that information' source

Above, Anomalocaris size via wikipedia

It's unusual mouth parts made of wrinkled structures and sharp teeth, plus grasping appendages would have been ideal to catch and eat soft bodied animals like worms or comb jellies

Above, Radiodonta oral cones wikipedia........looking rather like an anus with teeth, imo

Above image by Junnn11

Anomalocaris fossils have been discovered in Canada (Burgess Shale), Australia (Emu Bay Shale), China and the US and include species

-A. canadensis Whiteaves, 1892

=A. whiteavesi Walcott, 1908

=A. gigantea Walcott, 1912

=A. cranbrookensis Resser, 1929

-A. daleyae Paterson, García-Bellidob & Edgecombe, 2023 wikipedia

Plus 8 other species including

- Anomalocaris saron, from the Chengjiang lagerstatten in China source

Above, Anomalocaris saron, a Radiodonta from the Chengjiang Biota, China

The Anomalocaris died off towards the end of the Cambrian, during the Great Permian Extiction along with up to 90% of all other life forms

Above image by Dotted Yeti

All info from wikipedia, and also here, here and here

As always, I am not an expert, I just enjoy learning and sharing interesting things....Any mistakes- leave a comment and I'll edit my post

Title photo by Distinctly Average

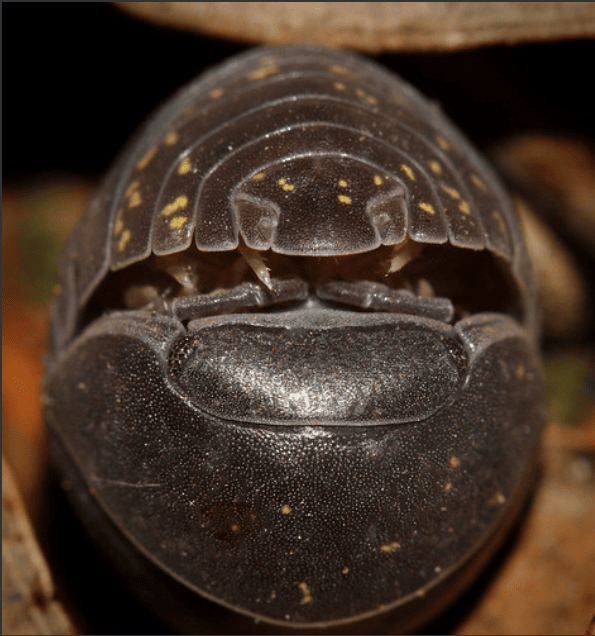

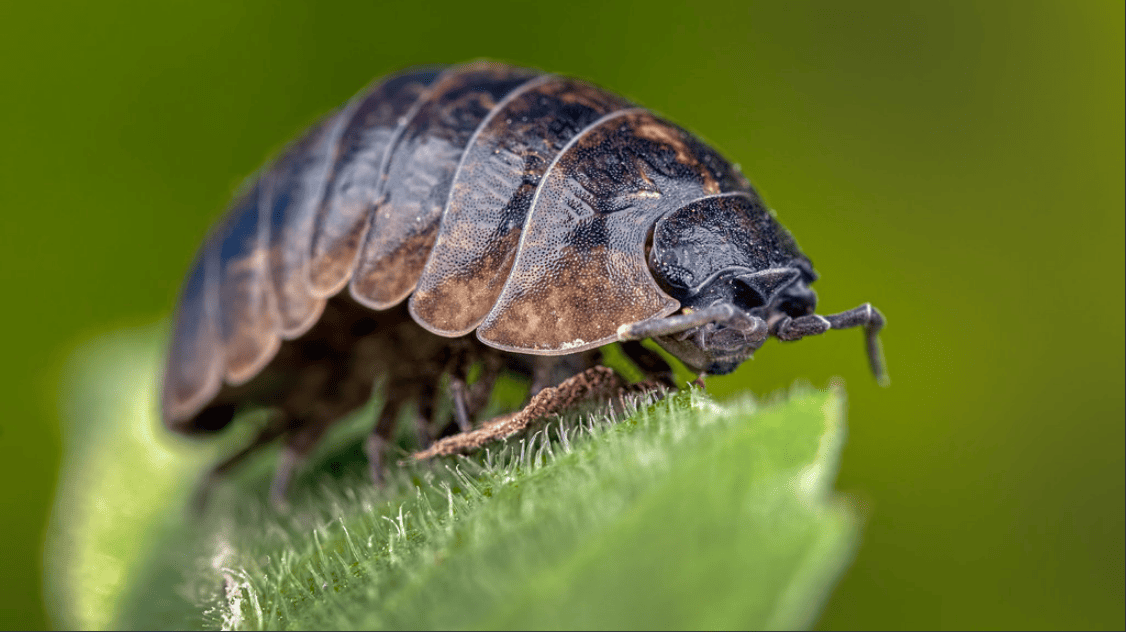

Woodlice are crustaceans, and get their name from being found in wood, and 'louse' (a parasitic insect) however, they are neither insects or parasites!

There are over 3500 species of woodlouse, and are found throughout the world except Antarctica

Above photo by Nico Ardans

Their ubiquity has resulted in many (up to 250) different local names for them including...

- Boat-builder (Newfoundland, Canada)

- Butcher boy or butchy boy (Australia, mostly around Melbourne)

- Carpenter or cafner (Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada)

- Cheeselog (Reading, England)

- Cheesy bobs (Guildford, England)

- Cheesy bug (North West Kent, Gravesend, England)

- Chiggy pig (Devon, England)

- Chisel pig

- Chucky pig (Devon, Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, England)

- Doodlebug (also used for the larva of an antlion and for the cockchafer)

- Gramersow (Cornwall, United Kingdom)

- Hog-louse

- Millipedus

- Mochyn coed ('tree pig'), pryf lludw ('ash bug'), granny grey in Wales

- Pill bug (usually applied only to the genus Armadillidium)

- Potato bug

- Roll up bug

- Roly-poly

- Slater (Scotland, Ulster, New Zealand and Australia)

- Sow bug

- Woodbunter

- Wood bug (British Columbia, Canada)

- Wood pig (mochyn coed, Welsh) source

Above photo by mark faux

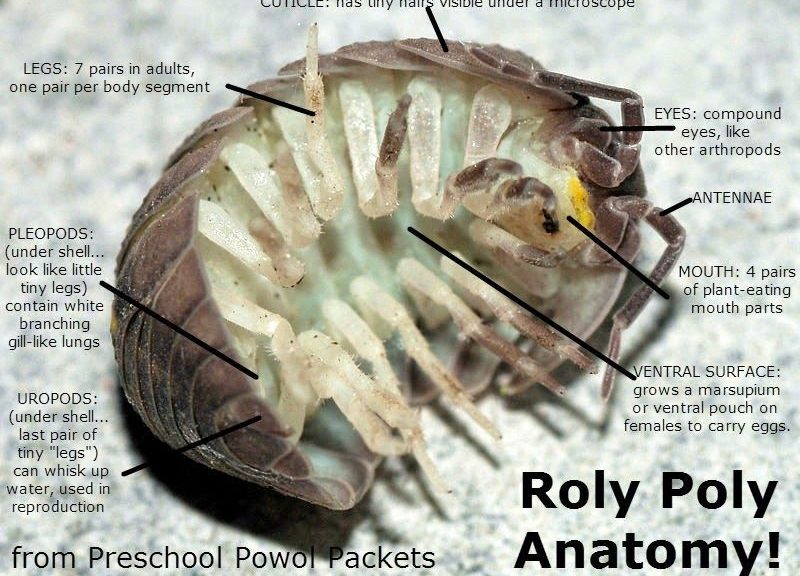

They have dark grey or black shells, with armour like exoskeletons made of 7 plates. Each plate has ~~2 pairs~~ one pair of legs attached, making 14 legs in total. They grow between 0.7mm to 18mm, and can live up to 2-3 years!

Above photo by davholla2002

Their main defensive behaviour is to roll up into a ball, and they can also release an odourous chemical to deter predators. They will also 'ball up' in order to prevent dehydration, and moisture loss during dry periods!

Above photo by Jim McLean

They are living fossils! Their aquatic ancestors lived in the oceans during the Silurian and Devonian periods. Later on, probably during the Carboniferous, they had evolved to live on land

Above photo by Sam

During this aquatic to terrestrial transition they had to evolve a brood pouch (marsupium) to prevent their eggs and young from drying out (Their ancestors would have released eggs directly into the water).

Above photo by Brian Valentine

Another adaptation is breathing via their gills which are located on their hind legs and are always covered with a thin layer of water. As a result they have to live in moist, damp environments. They also prefer to live in groups!

Image source

They eat decaying leaves, fungus, mold, and even the droppings of other animals. They help to break down vegetation and organic matter and play an important role in the nutrient cycle!

Above photo by Siew Chuan Cheah

They need to shed their exoskeleton as they grow, and this molt takes place in two stages. Firstly, the back half is lost, then about 2-3 days later, the front half sheds. Most other athropods shed their cuticles in one go

Above photo by Max Thompson

Woodlice can tolerate contaminated soil, unlike most other creatures!

....they can crystallise heavy metal ions midgut like copper, zinc, cadmium, arsenic and lead. This cleans up soil and purifies contaminated water. source

Aren't they fab?

Above photo by David Graham

All information from wikipedia here and here unless stated otherwise

As always, I'm not an expert, I just like sharing fun things....also this is my first post with my new mander account....woooo!

edit- 'one pair of legs'

Title photo by Robin Procter

It is one of the most common hawk moths in the UK and Europe

It gets its name as the caterpillar is said to resemble an elephants trunk

Above photo by Pete Hawkins showing the brown variation of caterpillar

It is one of the most colourful moths sharing the same colouration with the smaller Small Elephant Hawk Moth

Above photo of Large and Small Elephant Hawk Moths from here

It flies mainly in a single generation between June and September but with an occasional small second generation recorded in the south source

....active at dusk. It is commonly found in parks and gardens, as well as woodland edges, rough grassland and sand dunes source

Above photo by Heath McDonald

Its caterpillars feed on the leaves of willow-herbs, fuchsia and bedstraw. The adults are nocturnal feeders of flowers that open, or produce nectar at night. It can hover whilst feeding

Above photo by Rolf Nagel

There is usually only a single generation in a year, although occasionally there may be small second generation recorded in the south

The female moth release a sex pheromones in order to attract a mate

Above photo by Richard Collier

Above photo by Pablo Martinez-Darve Sanz

After successfully mating the female lays eggs either singly, or in pairs on their preferred food plants (willow herb, bed straw, and some garden plants like fuchsias, dahlias, and lavender). The eggs hatch within 10 days

Above photo by Wolfgang Burens

The young caterpillars start off as yellowish white to green, then changing to a brown-gray colour with black dots along the length of the body when they have finished growing. There is often a green version of the full grown caterpillar. They reach approximately 3 inches long

Above photo by Barry Forbes

Above photo by Nigel Pugh

Above photo by Beate

It takes about 27 days for the caterpillar to be ready to pupate. They find a secure spot usually at the base of a plant in debris, or underneath the ground. They then overwinter as a pupae!

Above photo by Roger Wasley

Above photo by Richard Collier

Above photo by David

All information via wikipedia unless otherwise stated

Title photo by Mick Talbot

The Common Earwig belongs to the order Dermaptera, which is Greek for 'skin wings', The name 'Earwig' comes from the Old English words for 'Ear Beetle'. Entomologists believe the origins for the name refer to their wings, which look like an ear when unfolded. The species name 'auricularia' is a specific reference to this, and 'Forficula' comes from a Latin word for 'little shears' or 'scissors'.

Despite their wings being fully developed, they are weak and rarely used, if they are found in the home on walls or on the ceiling they prefer to drop to the floor and scurry away

Above, photo by Marc Kummel

Above, Illustration of common earwig with wings extended. Source

Earwigs don't purposefully climb into human ears, although there are anecdotal reports of the occasional earwig being found there. They certainly do not lay their eggs in human brains, and the old wives' tale is just superstitious nonsense

Above photo by hedera.baltica

The Common Earwig is found throughout Europe and Britain, it has also been introduced to North America, and accidentally to New Zealand. They prefer cool, moist habitats, and are mainly active at night. During the day they hide in inaccessible places like flowers, fruits, wood crevices

Above, photo by Christian HUGUES

They are omnivores, but rarely hunt for prey, referring to scavenger instead. Their diets include plant matter (their favourites being Hedge Mustard, White Clover and Dahlias) and small insects including aphids, spiders, insect eggs

They have elongated, flattened brownish coloured bodies, and are approximately 12-15mm long. Both sexes have forceps like cerci (forceps- paired appendages on the rear of many arthropods). The males cerci are large, robust and curved, whereas the females are slender and straighter. The cerci are used in courtship displays, as tactile stimulus for the females during mating, as well as for feeding and self defense.

Above, photo of male and female by Tim Ransom

Both F. auricularia males and females take an active role during courtship. The males starts to display by bobbing or waving his cerci. If the female is receptive, both the male and female will progress to tactile stimulation, with the males using their cerci to encircle the female. It's worth noting that the males do not aggressively use their cerci to hold the female in place during mating.

Above, photo by zosterops

Courtship continues with abdomen arching, bobbing and twisting, before mating occurs. Male cerci are necessary for mating, and those whose cerci were removed were unable to find a mate In order to mate the male and female face opposite directions, with the males cerci under the tip of the females abdomen. If undisturbed the mating pair can remain joined for many hours, with the female often moving around to feed.

F. auricularia will look after both her eggs and provide additional care to her young and rarely feeds during this time. The female lays around 50 eggs in a small underground nest, 5mm below ground during Autumn. Entering a dormant state she stays with them throughout Winter. She cares for her eggs by cleaning them with her mouth and cerci, removing pathogens and fungi. She will defend her nest fiercely and relocate her eggs to a safer place if necessary

Above, photo by Nikola Rahmé

In Spring the young hatch, and their mother continues to care and protect them. She will groom, provide food and even regulate the temperature of their nest. As they grow from larvae to first instar stage they are also taken by her on night time foraging excursions. She continues to guard them until they are around one month old and have reached maturity

Above, photo by Thomas J Astle

Common Earwigs also demonstrate altruistic behaviour by accepting foreign offspring and eggs and providing the same level of care as they do their own. It is not the case that they don't recognise the difference between their own and another's, as each mother regularly applies an aromatic chemical to her eggs and this chemical is family specific

Above, a molting earwig, by Marcello Consolo

Both male and female Common Earwigs produce pheromones, which help them to find suitable group shelters to hide in during the day. These group shelters can be as many as 50-100 individuals per square meters which can encourage fungi, bacteria and also attract predators. It has been observed that having some feces in the nest site as it can have pathogen inhibiting properties, and feces eating can help with the transfer of gut bacteria and help if food is scarce

Above, photo by Ireneusz Irass Walędzik

All information from here, here and here

As always my disclaimer- I am not an expert, I just like finding and sharing interesting things. Any errors please leave a comment and I'll edit my post. Cheers!

cross-posted from: https://lemmy.ml/post/12435180

NB This is a post I did on awwnverts and decided to add it here. I've included some extra photos of ol' Eunice, as I wanted to show how beautifully iridescent it is, as well as some really nice (glamorous) head shots!

Post image 'Bobbit-Worm' by Hendra Tan

Their name comes from the John and Lorena Bobbit Case

They live tropical and subtropic bodies of water in the Indo-Pacific. They've been discovered in Bali, New Guinea, the Philippines, Australia, Fiji, and Indonesia!

They can reproduce asexually via segmentation!

Photo by budak

They can live between 3-5 years and grow on average 3 feet long, although one was discovered at 10 feet long!

Photo by Ken Traub

The fossil record shows they've been around for 20 million years!

They like to build mucus lined burrows on the sea floor from where they ambush their prey!

Photo by eunice khoo

Despite having a pair of small eyes they use their antennae to detect prey as they are virtually blind!

Photo by Ken Traub

Peters' Monocle Bream tropical fish have been observed 'mobbing' Bobbit Worms by directing sharp jets of water at them in order to deter their attacks!

Bobbit Worms can decimate aquariums. They can arrive as small worms hidden in rocks and corals and can remain undetected for quite some time. Don Arndts heroic battle against a Bobbit Worm is the stuff of legends. His foe was a wily adversary despite the many attempts to poison and kill it, including glue and crushed glass hidden in baited shrimp! TLDR version here

Their jaws are wider than their bodies are retractable and open like scissors!

Photo by Anilao~Critters

Their bodies are covered in tiny bristles which grip, and help it to explode out of it's burrow while hunting!

Mr DeMille, I'm ready for my close up...

Photo by Rob_Lee Photography

Now give the little fella a kiss!

(photo by Pauline Walsh Jacobsen)

edit- most info from here and I forgot to credit the last image

Title photo 'Cuthona yamasui, Tulamben,bali,indonesia' by Yansu JunK

Nudibranch, meaning 'naked gills' are an order of marine gastropod of over 3000 species! They breathe through a ‘naked gill’ shaped into branchial plumes (simillar to the alveoli of a human lung) but external to their bodies

Above, 'Ocellated Phyllidia, Phyllidia ocellata, Alor, Indonesia' by Jeremy Smith

They are soft bodied, slug like creatures and are noted for their bright colours and extravagant body forms. Their nicknames reflect their fabulous forms- "clown", "marigold", "splendid", "dancer", "dragon", and "sea rabbit"

Above, 'Flabellina affinis' The Mediterranean by Verheyen Stefan

They are found worldwide including the Arctic and Antarctic, through temperate to Tropical sea waters (though some species can live in brackish waters) They can be found at all water depths from warm shallow reefs (where the greatest number of species are found) to depths of 700 metres. One species was discovered at a depth of 2500 metres!

Above, 'Nembrotha kubaryana). Lembeh, Indonesia' by Trent Burkholder

Species can vary in size from 4mm to 40cm long, and are oblong in shape. They can also be thick or flattened, long or short, ornately colored or drab to match their surroundings!

Above, 'Hermissenda crassicornis, Point Defiance Marina, Tacoma' by Zachary Hawn

Their eyes are small and simple, and can only discern differences in light and dark. Instead they have tentacles on their heads which act as sensory organs being sensitive to touch, taste and smell!

Above, 'Ceratosoma trilobatum, Indonesia, South Molucces - Ambon' by divemecressi

They are carnivorous predators, usually feeding on sea sponges, anemones, corals and barnacles, although some are cannibalistic!

They have evolved defense strategies to protect them from being eaten, including camouflage to look like sea sponges, chemical defenses complete with warnings. Some species eat hydrozoids (a relation of jellyfish) and then store the stinging cells that pass undigested through their gut to their rear end...any predator trying to bite one of these nudibranchs will end up with a painful sting!

Above, 'Phideana hiltoni' by Ken Bondy

They are hermaphrodites (both male and female) and their sex organs are on the right side of their bodies. They still need to reproduce sexually though. When they meet a suitable partner they will engaged in a 'courtship dance' lasting for a few minutes. They then lay eggs in a long slimy ribbon, from as few as a couple to up to 25 million! source

Above, 'Consummation' by lee Ming

Above, 'Threesome having fun, Lamprohaminoea cymbalum, Tulamben Bali' by Ludovic

More nudibranchs to enjoy.....

Above photo by Jackson Wong

Above, 'Halgerda tessellata, Philippines - Malapascua' by divemecressi

Above photo by Carol Buchanan

Above photo by Barbara Stevens

Above photo by Joan Ribas

All info from here, here and here

As always, I'm not an expert I just like sharing fun things....any errors leave a comment, and I'll edit my post, cheers!

edit, link

Title photo- life reconstruction of Aysheaia pedunculata

Travel back in time to the Cambrian Era, a period famous for the diversity of its life forms!

Lasting approximately 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 million years ago (mya) to the beginning of the Ordovician period 485.4 mya. It is a period where the atmosphere had elevated concentrations of oxygen, and the global temperature increased-creating a temperate world

Geological timescale from here

Scientists believe that the higher oxygen levels, and warmer climate contributed to the incredible diversity of life that occurred in the oceans.

However, on land it was mostly barren...complex lifeforms were non-existant and would have been restricted to mollusks and athropods emerging from the water to feed on micobes in slimy biofilms

The Cambrian is unique as it had unusually high deposits of lagerstätte sedimentary deposits, these sites offer exceptional preservation of 'soft' organism parts, as well as their harder shells which means that the study and understanding of the fossilized life forms surpasses some of later periods

Which brings us to Aysheaia!

It is an extinct genus of soft-bodied lobopodian, known from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale of British Columbia, Canada source

Described as looking like a 'bloated caterpillar' with spines. It was a segmented worm like animal 1 to 6 cm in length and about 5 mm wide

Comprised of 10 body segments with each segment having a pair of spiked annulate legs (consisting of rings or ringlike segments). It did not have a separate head, its mouth occupied the front of the body along with 6 finger like projections, and 2 grasping limbs on it's 'head'.

Diagrammatic reconstruction of Aysheaia pedunculata

Reconstruction of A. pedunculata

It was similar to modern terrestrial Onychophora (velvet worms). However, it differs due to a lack of jaws and antennae, and possible lack of visual organs, and the terminal mouth...

Above, Photo of Velvet Worm (Euperipatoides sp.) by Stephen Zozaya

Aysheaia is believed to have grazed on prehistoric sponges gripping onto them with it's many claws. The shape of it's mouth suggests that it was a predator. It probably used the paired structures on it's head to grasp hold of its prey, and then pass it to the finger like projections around its mouth

And now for some fossils!

Above, Lobopodian Aysheaia pedunculata Walcott, 1911, USNM 365608 from the Stephen Formation (Cambrian Series 3, Stage 5), British Columbia, Canada here

Above, Aysheaia pedunculata (ROM 61108). Complete specimen preserved laterally showing limbs and gut trace. Specimen length = 20 mm here

Above, Aysheaia, a worm-like animal with annulated legs, from the Burgess Shale, Canada here

Also this really awesome diorama of life under the Cambrian sea

Above, Burgess Shale Biota (L-R) Aysheaia, annelid worms, Olenoides trilobite, Marrella here

Well I hope you enjoyed this post (hopefully the first of many) of ancient invertebrates, and as usual my disclaimer that I'm not an expert, I just like sharing fun things!

All information via wikipedia here and here, and not wikipedia from here and here

edit, formatting

edit 2- Done the thing that makes the images pop out in order to link this post with one on Velvet Worms...

....and a big 'Hello!' to you, if you've just read this post after following the link 😊

Title photo by Kristen Rudd

There are over 7000 species of worm, of which 150 are widely distributed around the world!

Their bodies are made of many ridged segments covered in tiny bristle called 'setae', which help them grip the substrate allowing them to move forwards and backwards!

Photo by John Hallmén

They eat organic plant matter, fungi and other microorganisms!

Earth worms breathe through their skin, can breathe underwater and survive being submerged for quite some time!

They secrete mucus which helps them move through the soil and by contracting and relaxing different muscles, which alternates shortening and lengthening their bodies!

Photo by Aisling

Earthworms are mostly hermaphrodites (having both male and female sex organs), although recently a (nematode) worm was discovered that had 3 sexes, 1 part male, 1 part female, and 1 part hermaphrodite (it also lives in water 4 times saltier than the ocean and is immune to arsenic!)

One study found that worm sex can last between 69-200 minutes!

Both worms will get pregnant during sex, and each worm will use both their sex organs at the same time!

Photo by Reds.

Photo by Bob

Post exchange, each worm forms a collar-like clitellum around its body. This clitellum, filled with eggs and sperm, forms a cocoon when it’s pulled off. Inside the cocoon, fertilization occurs, resulting in hatchlings. via Bob

Each earthworm can produce up to 1000 baby worms every 6 months!

They are also capable of parthenogenesis, where they can reproduce asexually without the need for fertilisation

Earthworms will swallow tiny stones which they keep in their gizzard, these grind up vegetation and other organic matter to help digestion!

They have a closed circulatory system (like humans) which has 5 pairs of aortic arches which work together like 10 hearts to circulate blood- pushing it in one direction, then pulling in the other. (Most invertebrates have a simple pumping of fluids around an open system, which washes inside the body with blood extracting and exchanging nutrients and waste)

Earthworm Dissection by threeflowersphotography

Earthworms are Soil Engineers, their burrowing mixes soil, aerates substrate and converts complex organic matter into earthworm poo, which is then used by plants. They are critical to our growth of food and trees, without them soil density would increase, reducing the ability of roots to take up water and breathe!

Photo by John Glover

Earthworms have also been observed exhibiting social behaviour by forming herds and making 'group decisions' by using touch to influence each other!

....[They] tested how the worms affected each other's behaviour, investigating whether the worms use either chemical signals or touch to decide which chamber to move to....[Results] indicated that the worms did not leave a chemical trail behind them that communicated their direction of travel.... ......suggesting that they used touch to communicate where they were going. Source

Now give our worm friend a kiss!

Photo by Dave Buckley

All info from here and here, unless otherwise stated

Disclaimer! I'm not an expert, I just like learning and sharing fun things...any mistakes, leave a comment and I'll edit, Cheers!

edit, added (nematode) for clarification

No fun facts from me, but i like how when i tried to pick it up with a stick, it tilt its back toward the stick to protect its belly. Interesting creature!

Title photo by LS Perks

Native to Australia (where else?) it can also be found as an invasive species in New Zealand. It feeds on Eucalyptus species and can become problematic, striping the leaves and damaging the trees hence it's actual name The Gum Leaf Skeletoniser

As the caterpillar grows it sheds it's exoskeleton, during each molt the head portion of the previous exoskeleton stays attached to it's body resulting in a mini tower of empty heads

“The molted head capsules start stacking early but they are not always visible, as the smaller ones get dislodged over time,” Hochuli said. “It’s not uncommon to see caterpillars with at least five old heads stacked on top of the one they are currently using.” Source

The heads can reach up to 12mm tall, and look rather dandy!

Photo by Alan Henderson/Minibeast Wildlife

The several reasons for this, one is to look bigger and more intimidating to predators, another is to create a false target for a predator, and another is that the caterpillar uses the head piece as a weapon or shield to fend off insects with needle like mouth parts such as Assassin Bugs

....researchers removed the head stacks from some caterpillars, left them on others, and kept tabs on their survival once they were back in the field. Caterpillars who kept their extra heads were much more likely to survive in the field....Source

Photo by John Tann

Unfortunately for The Mad Hatterpillar it's list of predators is long and relentless.... it has also evolved stinging hairs to complement it's head gear, and will writhe around to evade being grabbed, and if that isn't enough it will vomit out it's guts....

“They’ll just spew out a whole bit of yucky green liquid that probably smells and tastes awful,” Henderson said. “And if they shove that in the face of the predator, it can turn them off.” Source

Photo by Betty AN

Once the Mad Hatterpillar is finished eating all the Eucalyptus it can, it pupates into a small brown, unremarkable moth with markings that help it camouflage on the trunks of it's food source

Photo by Victor Fazio

Title photo by Thomas J Astle (Possibly Zoosphaerium neptunus, Madagascar)

Giant Pill Millipedes (Sphaerotheriida) are found in Southern Africa, Madagascar, South and Southeast Asia, Australia and New Zealand. They like moist habitats in leaf litter on forest floors

They can roll into a ball if disturbed, smaller ones can be the size of a cherry, slightly larger ones can be golf ball. The largest which come from Madagasgar can be the size of an orange!

.....crunchy on the outside with a soft chewy centre....

Borneo Giant Millipede, Photo by Tristan Savatier

Sabah, Borneo, Photo by Thomas J Astle

Possibly Zoosphaerium neptunus, Madagascar. Photo by Thomas J Astle

The Giant Millipedes first and last dorsal plate align perfectly with no gap, making a tightly sealed ball which most predators can't open, however there are some including snails in South Africa which specialise in feeding on them. Also Meerkats and birds will hunt and eat them!

They are ground dwelling detritivores, and feed on dead organic matter, such as leaves and wood on the forest floor. They play an important role in decomposition helping to break down organic matter back into the soil!

A few Giant Millipedes can produce sound!

Sphaeromimus pill-millipedes live in the rainforests of southeastern Madagascar.....Males have a structure on their anterior telopod, known as the harp, which has several ribs and is able to produce sounds. This stridulation organ is still not well understood, but may play a role during courtship. Source

The name for them in the local language [in Madagasgar] is 'tainkintana' which means 'star droppings'!

Their antennae are very dexterous and mobile, and resemble elephant trunks as they probe their environment!

Sabah, Borneo, photo by Thomas J Astle

Their sex lives have 4 different phases....

The first phase is when a male detects a female, and orientates itself by positioning its anal shield towards the potential partner. Second, once the male is in contact with the female it starts to make stridulation sounds and vibrations. If the female recognises the male and is receptive, she will open up from her rolled-up position, or not roll up, and the male will then move below the female and grab her front legs with his telopods

The male then ejects sperm from his penises (he has one small penis at the base of each of the first pair of legs on the second segment), and transfers the sperm backwards along his legs and into the female opening which is on her second pair of legs. The two millipedes will then separate. After that, the female lays her eggs in the soil and covers them with a mud layer for protection. The eggs hatch into very small, pale pill-millipedes. Source

They are slow movers and are able to burrow into the soil and leaf litter. They also come in a nice variety of colours and patterning!

Photo by KancheongSpider

Photo by Mok Youn Fai

Agumbe Rainforest Research Station, Karnataka, India, photo by cowyeow

Possibly Zoosphaerium neptunus), Madagascar, photo by Thomas J Astle

Bothrobelum rugosum, Bau, Sarawak, Malaysia, Photo by bob5

Adult females have 21 leg pairs (42 in total), while males have an additional 2 leg pairs, which are probably used to grasp onto the females during mating!

Zoosphaerium neptunus, photo by Nicky Bay

.....draw me like one of your French girls.......

Zephroniidae, photo by Nicky Bay

Sphaerotheriida, Karnataka, India, photo by vipin.baliga

All info via wikipedia and Scientific American unless otherwise stated

Also I'm not an expert, I just like sharing fun things and critters, any errors let me know in the comments and I'll edit my post, cheers

Invertebrates

A community for general discussions about our friends that lack vertebrae